John Britten remembered

John Britten’s bikes mixed good looks with innovative engineering

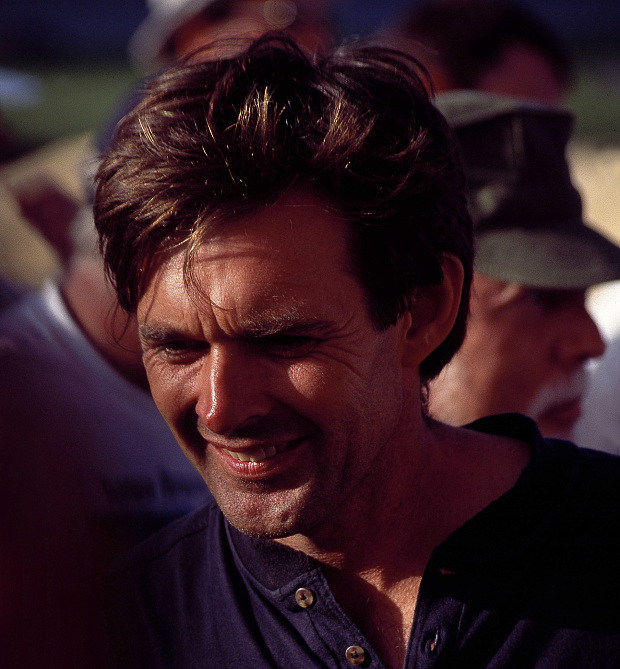

In this outstanding year for fast, technically advanced superbikes, today provides a reminder of a bike revered as one of the fastest and most advanced of all. September 5 marks the 20th anniversary of the death of John Britten, the maverick New Zealander whose essentially home-built V1000 racebike made an indelible impression with its performance, beauty and innovative engineering.

Ask any knowledgeable group of motorcyclists, “What’s the greatest bike ever?” and it won’t be long before the V1000 is mentioned. Only 10 examples of this 1,000cc V-twin were produced. Yet it remains an inspiration to many, including racer and TV star Guy Martin, one of the few to have ridden a bike that he describes as his all-time favourite.

Even now there is something futuristic about the V1000, with its flowing lines, unique chassis design and V-twin engine from which tumbles a serpentine exhaust system. It’s an elegant and purposeful looking machine. And in its early-Nineties heyday it was also competitive, thundering to more than 170mph at circuits including Daytona in Florida and Assen in Holland to win prestigious races and set a number of speed records.

Part of the V1000’s appeal was the back-story: handsome and charismatic engineer takes on the world with a machine that he’d designed, then built with friends in Christchurch. New Zealand’s south island was just about as far from most racetracks as it was possible to get. But if anyone epitomised the stereotype of the resourceful Kiwi it was Britten.

He was one of those rare individuals whose engineering ability was matched by an eye for style. At age 13 he and a friend had rebuilt an old Indian bike they’d found in a ditch. After training as an engineer he went into business as a fine artist, designing and making glass lighting. He converted a stable into a spectacular house and garage, casting the door handles himself because he couldn’t find any he liked.

John Britten epitomised the stereotype of the resourceful Kiwi

That independent spirit served Britten well when, after dabbling as a racer, he decided to build a bike. Almost every component was created from scratch, including the liquid-cooled engine. This produced more than 160bhp, very competitive at the time, and was sophisticated in its use of fuel-injection that could be fine-tuned via a laptop.

The chassis was even more radical, comprising little more than the engine with suspension parts and swing-arm bolted to it. Carbon-fibre was used extensively, including for the unique girder front suspension struts and even for the wheels, resulting in the bike weighing just 145kg. This was arguably the most technically advanced motorcycle in the world, and it looked it. Britten had glued together hundreds of pieces of wire to shape its carbon-fibre bodywork, which was normally finished in distinctive pink and blue.

The V1000 also handled well and achieved some spectacular victories against much better funded teams from Ducati and Harley-Davidson. Several follow-ups were built over the next few years, some incorporating refinements including a larger, 1,100cc engine. All were racebikes, although Britten was hired as a consultant by the then Australian-owned Indian firm, raising the enticing possibility that roadgoing derivatives might follow.

Instead, the Britten story ended tragically. First, rider Mark Farmer was killed in an Isle of Man TT crash on one in 1994. Then, the following year, Britten himself died of cancer, aged just 45.

Britten’s memory, however, lives on in that small series of V1000s, which are owned by museums and collectors, and occasionally ridden at events such as Goodwood’s Festival of Speed. Some key features – including monocoque chassis design, programmable fuel-injection and carbon-fibre construction – are incorporated in modern superbikes. We can only wonder what John Britten would be coming up with now, if he were still pushing the limits of motorcycle design in that remote New Zealand workshop.

Source: www.telegraph.co.uk